This essay explores the Salton Sea as a case study for the entwined relationship between human history and environmental context in shaping a novel ecosystem.

Executive Abstract

This essay explores the Salton Sea as a case study for the entwined relationship between human history and environmental context. In telling the inseparable histories of the Salton Sea and development in the Imperial Valley since the late-19th century, we are better able to understand three challenges posed by novel ecosystems: 1. Where to draw spatial boundaries around a novel ecosystem if we take into account the human and natural forces that shaped it; 2. How far back in history to refer to baseline conditions, given that “pristine” nature does not exist outside of history; and 3. How we might evaluate which novel environments are preferable.

The concept of novelty—the dissimilarity of natural and social systems relative to prior reference baselines—challenges us to understand how human and natural forces have conspired to create hybrid environments (Radeloff et al. 2013). By conceiving of novelty in terms of hybridity, we are able to see that human history and environmental context cannot be separated from one another (Sutter 2013; White 1995; Wilson 2010; Fiege 1999; Carse et al. 2016). This insight opens up several important questions that the methods and rigors of historical geographical perspectives are uniquely suited to answer: Where should we conceive of the spatial boundaries around a novel ecosystem if we take into account the hybrid forces that shaped it? How far back in history should we refer to baseline conditions, given that “pristine” nature does not exist outside of history? How are we to evaluate which novel environments are preferable, given that some ecosystems that seem natural have been heavily influenced by human activity, while others that seem to be dominated by human activity have shown signs of nature thriving?

Few places could be more emblematic of these questions than the Imperial Valley of southern California, a hybrid landscape where natural and human forces conspired to create environmental conditions with no historical referents. The history of the development of the Imperial Valley is inextricably linked to the history of the Salton Sea (deBuys 1999). The valley, situated along the San Andreas Fault, flooded episodically in past millennia, its flat playa between abrupt mountain ranges filling when water overcame the banks of the Colorado River. In 1908 engineers, using canals to divert the Colorado River to irrigate farms in the Imperial Valley that were newly connected to eastern markets via the railroad, created the Salton Sea when they accidentally sent the entire river flooding into the basin for two consecutive years.

Satellite image of Colorado River (NASA)

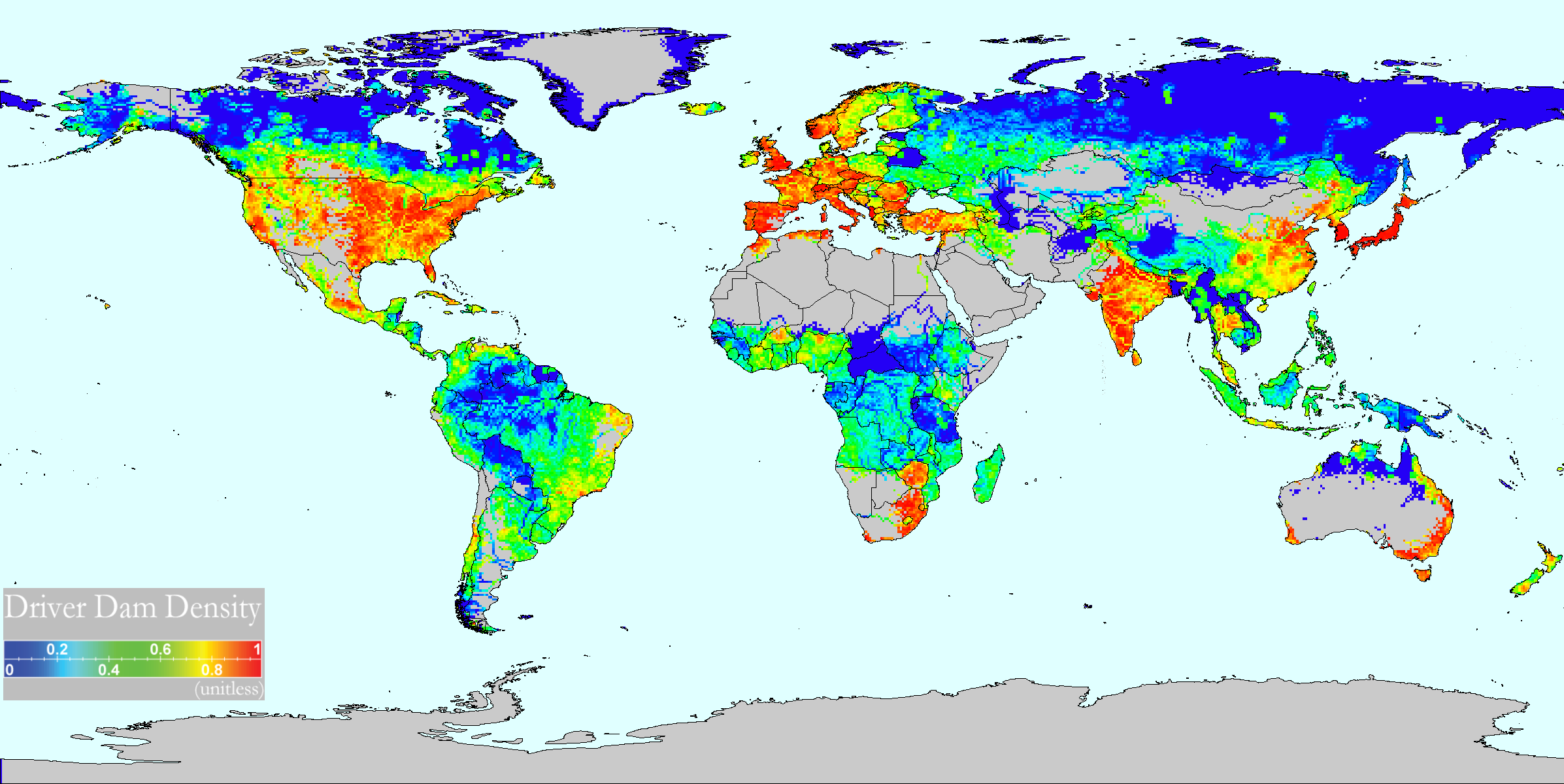

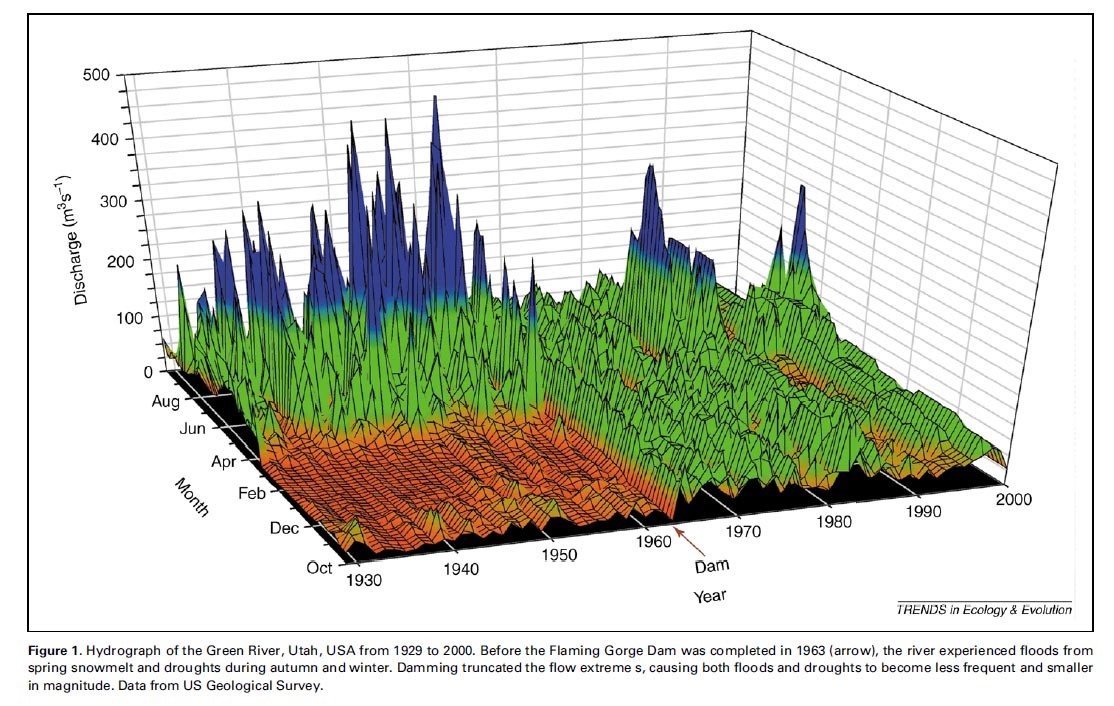

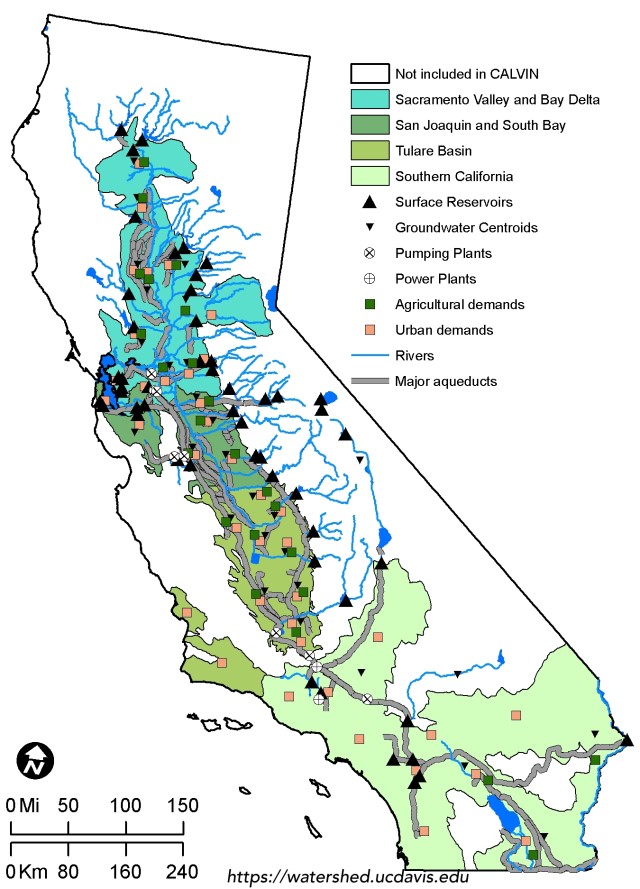

But this body of water would have evaporated long ago, just like the inland seas of millennia prior, were it not for developers and agriculturalists, who saw the potential to expand their farm operations into a vast inland agricultural enterprise in the Imperial Valley. They intervened by intentionally diverting and transporting water back into this inland sea, which served as a sump for agricultural runoff. Because the intricate network of dams, canals, and aqueducts ensured a consistent supply of water to the otherwise arid basin, because the climate was ideally suited to growing crops in the winter, and because the political economy of migrant labor, transportation networks, and capital investment allowed a burgeoning industrial farming industry to flourish, the valley became one of the most productive agricultural regions on the planet over the course of the 20th century (Andres 2015).

As a consistent water supply kept the Salton Sea filled, it became a destination for migrating birds along the Pacific Flyway and human tourists alike. Among the most diverse and significant populations of birds in North America wintered there. Human communities wintered there, too: in the decades that followed, developers envisioned the inland sea as serving an additional role beyond an agricultural sump as a recreational destination for tourists, and built a tourist economy around the sea in the 1950s and 1960s. But in the 1970s and 80s, it became clear that water diversions would not continue to sustain the sea level, and it began to drop as the dry air evaporated the water. As evaporation caused water levels to recede, the sea became progressively more hyper-saline, killing some populations of fish and birds while allowing others to thrive; birds continued to use the sea as crucial habitat along their migration routes.

Human communities who lived around the sea also experienced complex changes as environmental conditions changed. The salt, combined with chemicals from agricultural runoff, left a toxic crust on the lakeshore as the water receded, and the tourist economy couldn’t be sustained, even as agricultural production in the Imperial Valley continued to flourish. Now the main human communities who live around the sea are farm workers whose livelihoods depend on crop production. These communities are expressing concern over toxicity from airborne particles of dust from dry parts of the seabed, but the sea level continues to recede, the water continues to become more hyper-saline, and water deliveries will be suspended as of 2017 in favor of diversions to urban areas like San Diego and Los Angeles. It is unclear how long the system can be sustained.

Thus neither the Salton Sea nor the Imperial Valley would survive, or even exist, without the other. The system’s novelty is derived from its hybridity: the history of migrating waterfowl is inextricably linked to the history of irrigation. The production and global circulation of agricultural crops depends on the sea serving as a sump for agricultural waste. The gradual salinization of the Salton Sea depends on the annual snowpack in the upper Colorado River watershed and on global produce markets; on the infrastructure used to transport water over hundreds of miles and on the topography of southwest California; on western urban land use trends and on drought conditions; on soil fertility and on the political economy of border crossings for migrant workers. The Salton Sea exists within the Imperial Valley, the Colorado River Basin, the American West, and the global economy.

These hybrid relationships are rooted in deeply spatial and historical processes, and thus cannot be understood without contextualizing them over the period during which the Imperial Valley was constructed and the terms of its human management set. This deeper history can be obscured by both the contemporary debate over the need to “save the Salton Sea” and its dramatic “origin story,” even though the Imperial Valley became the plumbing for the sea. And this historical geographical perspective shows us that novel ecosystems display simultaneous and counterintuitive processes: human manipulations of seemingly natural environments can sometimes bring and sustain life, while seemingly natural processes can create unexpected consequences for human and wildlife communities alike.

~by Daniel Grant~

Further Reading:

Andres, B (2015). Power and Control in the Imperial Valley: Nature, Agribusiness, and Workers on the California Borderland, 1900-1940 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press).

Carse A et al. (2016) “Panama Canal Forum: From the Conquest of Nature to the Construction of New Ecologies.” Environmental History 0: 1-85.

deBuys W (1999). Salt Dreams: Land and Water in Low-Down California (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press).

Fiege, Mark. Irrigated Eden: The Making of an Irrigated Landscape in the American West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999).

Radeloff V et al. (2015) “The rise of novelty in ecosystems,” Ecological Applications 25: 8, 2051–2068.

Sutter P (2013). “The World With Us.” Journal of American History 100:1, 94-119.

White, Richard (1995). The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River (New York: Hill and Wang).

Wilson, R (2010). Seeking Refuge: Birds and Landscapes of the Pacific Flyway (Seattle: University of Washington Press).